Best Infosec-Related Long Reads of the Week, 2/4/23

The line Conti wouldn't cross, The Kremlin spies on Telegram?, Hackney Council's ransomware pain, Spyware threatens democracy, Pig butchering's UK nexus, Truckers' surveillance woes, more

Metacurity is pleased to offer our free and paid subscribers this weekly digest of the best long-form infosec pieces and related articles that we couldn’t properly fit into our daily crush of news. So tell us what you think, and feel free to share your favorite long reads via email at info@metacurity.com. We’ll gladly credit you with a hat tip. Happy reading!

When Hackers Hobbled Ireland’s Hospitals, They Took Themselves Down, Too

Bloomberg’s Ryan Gallagher explains how a life-threatening ransomware attack on Ireland’s public health system in May 2021, which compromised 54 hospitals and 4,000 other medical facilities, the largest ever such attack on a health care system, forced the formerly ruthless Russia-based Conti ransomware gang to drop its $20 million ransom demand and discover a line it would not cross.

At the time of the HSE hack, Conti didn’t have a record of restraint. The FBI estimated that as of January 2022 the group had carried out attacks on more than 1,000 victims, receiving over $150 million in ransom, and the US Department of State is offering a $10 million reward for information leading to the identification of any of the people who had led it.

But security experts say they’d been picking up signs of discord over what behavior was acceptable. “We knew what was happening inside the group” as the attack was going on, says Richard Browne, director of Ireland’s National Cyber Security Centre, which investigated the attack. Browne’s team had identified a subsidiary, which it suspected was based in St. Petersburg, Russia, that had developed IcedID, a malicious software hackers have used to penetrate corporate networks in other attacks. “This actor group was younger, more aggressive and less risk-averse,” he says. “Our assessment is that they made themselves very unpopular within the group.”

Browne says he even has names of the specific people he suspects were involved in the attack, though that does little good so long as they stay in Russia. (His investigation also concluded that the hackers didn’t do a great job of covering their tracks and that the HSE’s security team should have realized it had been compromised when Conti first gained access to the network in March.)

How exactly the queasiness within Conti over the HSE hack developed into a decision to call it off remains mysterious. “It exposed them to a type of attention that they might not have wanted domestically, commercially or internationally,” Browne says. “I suspect it was the case here, where they cut their losses and ran.”

The Kremlin Has Entered the Chat

Wired’s Darren Loucaides tells the story of how Russian anti-war activists discovered that Telegram, a supposedly anti-authoritarian communications app co-founded by Russian native Pavel Durov, might be complying with the Kremlin’s requests for access to users’ messages.

Over the past year, numerous dissidents across Russia have found their Telegram accounts seemingly monitored or compromised. Hundreds have had their Telegram activity wielded against them in criminal cases. Perhaps most disturbingly, some activists have found their “secret chats”—Telegram’s purportedly ironclad, end-to-end encrypted feature—behaving strangely, in ways that suggest an unwelcome third party might be eavesdropping. These cases have set off a swirl of conspiracy theories, paranoia, and speculation among dissidents, whose trust in Telegram has plummeted. In many cases, it’s impossible to tell what’s really happening to people’s accounts—whether spyware or Kremlin informants have been used to break in, through no particular fault of the company; whether Telegram really is cooperating with Moscow; or whether it’s such an inherently unsafe platform that the latter is merely what appears to be going on.

The Untold Story of a Crippling Ransomware Attack

Wired’s Matt Burgess tells the story of the Pysa ransomware gang’s attack on Hackney Council, one of London’s 32 local authorities and responsible for the lives of more than 250,000 people, and how two years later, the Council is still dealing with the “colossal aftermath” of the event.

All the systems hosted on Hackney’s servers were impacted, [Hackney Council Strategic Director Rob Miller] told councilors at one public meeting assessing the ransomware attack in 2022. Social care, housing benefits, council tax, business rates, and housing services were some of the most impacted. Databases and records weren’t accessible—the council has not paid any ransom demand. “Most of our data and our IT systems that were creating that data were not available, which really had a devastating impact on the services we were able to provide, but the work that we do as well,” Lisa Stidle, the data and insight manager at Hackney Council, said in a talk about the council’s recovery last year.

One person living with disabilities in Hackney, who asked not to be named for privacy reasons, says they applied for social care at the end of June 2021—eight months after the cyberattack first hit—but didn’t end up with a care plan or visits from carers until February 2022. “I could not wash myself. I couldn’t wash my own hair,” they say. “And the reason for that delay, they repeatedly told me, was the hack.” The person recalls that when they first heard back from the council, months after initially getting in touch, the worker they spoke with was relieved they were still alive, as their situation hadn’t been clear and there had been a delay in the case.

The Autocrat in Your iPhone

Ron Deibert, Professor of Political Science and Director of the Citizen Lab at the University of Toronto’s Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy, examines in Foreign Policy how a global market for spyware, such as NSO Group’s notorious Pegasus spyware, has become an irresistible tool for both autocratic regimes and democracies alike, threatening democracy across the world.

One of the technology’s most frequent uses has been to infiltrate opposition movements, particularly in the run-up to elections. Researchers have identified cases in which opposition figures have been targeted, not only in authoritarian states such as Saudi Arabia and the UAE but also in democratic countries such as India and Poland. Indeed, one of the most egregious cases arose in Spain, a parliamentary democracy and European Union member. Between 2017 and 2020, the Citizen Lab discovered, Pegasus was used to eavesdrop on a large cross section of Catalan civil society and government. The targets included every Catalan member of the European Parliament who supported independence for Catalonia, every Catalan president since 2010, and many members of Catalan legislative bodies, including multiple presidents of the Catalan parliament. Notably, some of the targeting took place amid sensitive negotiations between the Catalan and Spanish governments over the fate of Catalan independence supporters who were either imprisoned or in exile. After the findings drew international attention, Paz Esteban, the head of Spain’s National Intelligence Center, acknowledged to Spanish lawmakers that spyware had been used against some Catalan politicians, and Esteban was subsequently fired. But it is still unclear which government agency was responsible, and which laws, if any, were used to justify such an extensive domestic spying operation.

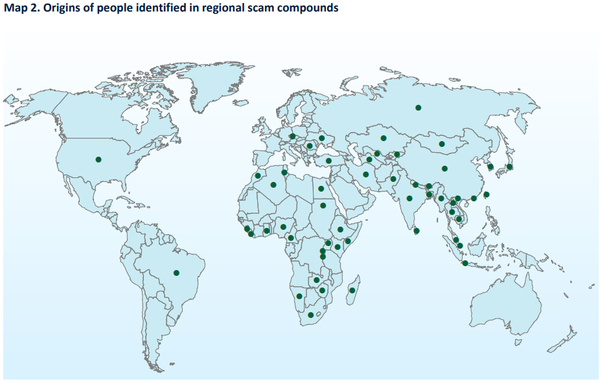

‘Everything is fake’: how global crime gangs are using UK shell companies in multi-million pound crypto scams

Shanti Das and Niamh McIntyre in The Observer share the results of their investigation that found international organized crime gangs are using the UK as a virtual base for their operations to conduct heartbreaking pig butchering scams by systematically exploiting lax company registration laws to carry out their frauds on an industrial scale.

Analysis has identified 168 UK companies accused of running fraudulent cryptocurrency or foreign exchange trading schemes, with around half of these likely to be linked to pig-butchering scams.

Registered to addresses including an empty shop in Croydon, a flat above a Chinese takeaway in Somerset, and a council flat in an east London tower block, dozens of the firms share an address, an office or are linked through domain registrations, indicating they may be connected. The vast majority of company directors are resident in China.

The companies do not appear to have genuine ties to the addresses where they claim to be based, and details about the real owners are scant. The fact the properties have been linked to frauds is often known to the UK authorities.

Yet despite extensive evidence of fraudulent activity, and concerns about the potential for earnings to be laundered via the UK, little has been done to tackle the scam companies – or to prevent new ones from opening.

The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Trucker

The New Yorker’s Gideon Lewis-Kraus delves into a new book by sociologist Karen Levy, Data Driven: Truckers, Technology, and the New Workplace Surveillance, that documents how extensively monitored truckers are by their employers using electronic logging devices in a way that goes far beyond federal mandates in a way that, among a host of detriments and indignities, increases trucking accidents. (And don’t miss this piece by Wired’s Andrew Kay, who hit the road in a big rig to find out how technology, corporate greed, and supply-chain chaos are making the lives of modern truckers miserable.)

The obvious objection is that these dignitary concerns, important as they are, seem irrelevant when weighed against the reality of highway fatalities; we might, as a society, consider this a reasonable trade-off, even if the truckers themselves bristle at the oversight. But, as so often happens, the attempt to impose an “apparent order” from above has seemingly backfired: the data from the first few years under the E.L.D. mandate have shown that the devices may lead to an increase in trucking accidents. The bulk of Levy’s book is devoted to explaining why the curtailment of personal judgment has had such poor results. For one thing, she says, imagine that your grandmother expects a visit to discuss your inheritance, and she knows it’s going to take you eleven hours to get to her home. Most of us would understand that to mean “about eleven hours,” and if taking a break for a coffee (or a 5-Hour Energy, or even one of the more advanced stimulants apparently on offer under the counter at some truck stops), or slowing down over a snowy pass, meant a half hour of delay, presumably Grandma wouldn’t mind. But if Grandma said that you had exactly eleven hours or she’d write you out of the will, Levy says, you’d drive “like a bat out of hell” to get there.

Global Technology Products, US Security Policy, and Spectrums of Risk

Justin Sherman, a nonresident fellow at the Atlantic Council's Cyber Statecraft Initiative and a senior fellow at Duke University's Sanford School of Public Policy, examines in Lawfare blog how tech-driven security questions go beyond TikTok and other policy dilemmas related to China and advocates for a more nuanced and longer-term vision for identifying and mitigating possible security risks associated with non-U.S. tech companies, products, and services.

Digital technologies can pose a variety of risks to U.S. security interests, including based on the technology product or service in question (from telecom equipment to mobile apps), its presence in or connection to the United States (from physical infrastructure to online ad entanglements), and the country of incorporation of its owner, among many others. Point being: Not every tech company, product, and service poses the exact same set of risks. The risk scenarios themselves might vary, such as the risk of a backdoor installation versus the risk of internet traffic hijacking. And the likelihood and severity of those risk scenarios can vary too.

Because of this inherent variation, policy approaches that categorically deem every technology company, product, and service from a country a “risk” often erase these distinctions. Policymakers need to consider whether their proposed policy approaches allow for the identification of a variety of possible security risks—and the development of a range of possible risk mitigation responses.